The Celtic Star

·28 dicembre 2024

Celtic in the Thirties: Unpublished works of David Potter – Jimmy McMenemy

In partnership with

Yahoo sportsThe Celtic Star

·28 dicembre 2024

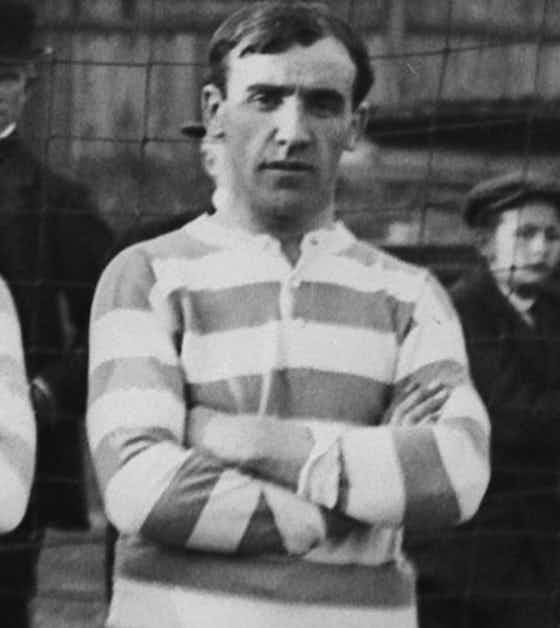

Celtic’s Napoleon Jimmy McMenemy, image by Celtic Curio for Celtic in the Thirties, available at Celticstarbooks.com

Whoever it was who suggested Jimmy McMenemy to come back to Celtic in October 1934 is also the man who won Celtic the Empire Exhibition Trophy. Whether McMenemy was Coach, Assistant Coach, Trainer or whatever, it was he who, in practice if not in theory, privately if not publicly, ran and organised the team in those momentous years of the late 1930s.

The Empire Exhibition Trophy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

Did Maley recommend McMenemy? We shall never know, but we can work a little of what was going on in the mind set of the Directors in 1934. Celtic in 1934 were failing. The few Scottish Cup successes of recent years – including the spectacular one of 1931 – did not really hide the impalatable truth that Rangers had won the Scottish League every year since 1927 apart from 1932 when Motherwell did it. It was now 8 years since Celtic’s last League win in 1926, and there had never before been such a barren spell.

Yet it was difficult to sack Maley. In the first place, this was not an era in which Managers were sacked at the drop of a hat. And moreover, he could not really be described as a total failure in the grand scheme of things. There were factors over which he had no control – economic depression, the tragedies of John Thomson and Peter Scarff, the sometimes frighteningly sudden rise of Rangers (based on naked religious bigotry) under the man called, not without cause, “ruthless Struth”.

But the main factor was that Maley was so well ensconced in his job. He was on good terms with the Directors – although the relationship was fraught on occasions – understood very well the broader picture of the financial side of the club, and remained a committed Celt.

Celtic Trainer Jimmy McMenemy with Abdul Salem

So he would have been difficult to dislodge and the end result and his replacement might well have been something that the Directors did not want. But it was also clear that he needed someone to help him and to support him without challenging him. Jack Qusklay had been a first class trainer but no Coach, and he had now gone in any case. It needed to be someone that Maley got on with – perhaps one of his great players of the past. Sunny Jim would have been ideal, but he had been killed in a motor bicycle accident ten years ago. Patsy Gallacher was too much of a rebel, Jimmy Quinn was a possibility but still (incredibly) too shy and socially inadequate – but there was still the great Jimmy “Napoleon” McMenemy.

McMenemy was still seen around frequently, still mad on football and a keen follower of his family who were currently adding to the family silver – John who had had a brief and not always happy time with Celtic, was now starring with Motherwell and was the proud possessor of a Scottish League medal in 1932, and Harry had won an English Cup medal with Newcastle United in the same year. Besides, in the same way that he was a very intelligent man on the playing field, he was also far from thick off it. He was also quiet, modest and humble.

Peter Wilson, John Thomson, Jimmy McStay, Jimmy McMenemy, Willie McStay, A Thomson, Jimmy McGrory. Photo The Celtic Wiki

In a word, he appreciated the situation. He had always been a favourite of Maley (and he had put up with Maley for 20 years!) and it was he who was accredited with his suggestion to Maley in 1912 which involved himself moving to inside left and thus allowing the prodigiously talented Patsy Gallacher to come in at inside right. The League and Cup double of 1914, and the consistently fine side of World War One had been built on that idea.

He was by nature a self-effacing man. He knew how good he was, but he never pushed himself forward for anything, always content to stay in the background and always being very supportive of others, constantly singing the praises of Gallacher, Somers, Quinn and Loney while others of course knew that he, Jimmy McMenemy, was as good as any of them.

McMenemy would be very careful now to make sure that Maley was still the Manager and still seeming to run the team. Under the guise of keeping him informed about injuries, he would make a few tactful suggestions about who should play on Saturday etc. but Willie Maley was still the manager. Basically, Maley got on with McMenemy, and McMenemy got on with Maley.

Celtic in the Thirties – Volume One

Celtic in the Thirties – Volume Two

Maley, for his part, also read the situation well. He could be brusque, awkward and cantankerous with most people, not least the Directors, and certainly with opinionated or uppity players. He could put most people in their place, but like all clever dictators, he knew that there are some people whom it does not do to upset. Members of the Press were in that bracket – he knew to keep them on side – and Jimmy McMenemy was another. No doubt, Napoleon would occasionally get his nose bitten off if he caught him at the wrong time, but there were be no lasting offence.

And what a knowledge of football McMenemy brought with him! He had of course been part of the greatest football team there had even been, and one cannot be beside so much talent (as well as allowing for his own ability, of course) without picking up a certain knowledge of the game! He had won the Scottish League six years in a row, and after a brief pause, four years in a row, and then in yet another remarkable season of 1918/19 he had recovered from Spanish flu (from which he very nearly died in November 1918 a week after the armistice) to come back and take the team to yet another League title!

He won the Scottish Cup in 1904, 1907, 1908, 1911, 1912 and 1914 and then at the end of his career won yet another with Partick Thistle in 1921, beating, of all people, Rangers at Parkhead! And that is before we talk about the Glasgow Cup, the Glasgow Charity Cup and the mighty goal that he scored for Scotland against England in 1914 – a story that got a good airing on many a winter’s night in a freezing trench in the next few years.

David Potter’s book on Jimmy McMenemy

So, he was a magnificent player. But we all know, don’t we, that magnificent players are not always great coaches. Jimmy McGrory springs to mind. And often great coaches/managers weren’t always brilliant players – Jock Stein, Sir Alex Ferguson (and dare one include Walter Smith in that category?), but McMenemy was both. Maley had once said that to Napoleon, the football field was like a chess board. In some ways, it was a strange analogy, but he meant that McMenemy could always see that one action led to another. This was perhaps why he was called “Napoleon”.

There was one way in which Napoleon made an instant difference. The forward line of Delaney, Buchan, McGrory, Crum and Murphy was not as good as Bennett, McMenemy, Quinn, Somers and Hamilton nor McAtee, Gallacher, McColl, McMenemy and Browning – but the potential was there. McMenemy remembered that one of the key things about the great forward lines in which he played was that they could interchange position. They were all well-trained – and that was certainly his job now – and could move about at speed dragging their defenders this way and that and wreaking general enthusiasm.

He knew that full backs were often described as “rugged”. It was a common enough term, and was a euphemism, along like other words like “robust” and “doughty”, for being hard tacklers who were not too particular about injuring opponents. But if there were any things that this breed of full backs and centre halves were not, such things were “speedy”, “mobile” and “adaptable”. It followed then that the wingers had to be fast, and if they could play on the other wing occasionally, then so much the better.

McMenemy was in luck. Jimmy Delaney arrived at about the same time as he did, and Frank Murphy who had been around for a year or two without impressing, suddenly came good under McMenemy. These two had the speed of greyhounds. Delaney was once bizarrely described as having the speed of “the fire brigade”, but there was more to him than that.

He was able to cut inside with the ball at his feet pulling a man with him, and when that happened Murphy could sprint across to the other wing, again with his marker on his heels, and the defence was so dis- orientated that McGrory could find space to await the final ball.

Jimmy “Napoleon” McMenemy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

1935/36 was the season of course in which the Scottish League at last returned, and Jimmy McGrory scored his famous 50 goals. Pictures were taken naturally enough with McMenemy and Maley sitting at either end of the front row. The headgear is significant. Maley has taken off his homburg hat, the better for the cameraman to see his face. He is unsmiling but clearly proud of his team who have now won their 18th League title and at the other side, sits McMenemy, well dressed with his suit and his bonnet. It would have been the way that he dressed on a Sunday, one imagines.

He was not the first Celtic man to be described as “just an ordinary man”. It was famously said about Jimmy Quinn by people who always assumed he was extraordinary until they saw him in ordinary clothes at a railway station, for example. Napoleon would walk around the streets of Glasgow, nodding to people, making a comment about the weather, talking to a child and not everyone would immediately know who he was. Famously, when he had won his Scottish Cup medal with Partick Thistle, he was asked what he wanted done with it “Ach, just pit it the box wi’ the ither wans!”

After a year or two, he had done enough to earn himself an Assistant Trainer. It could hardly have been a better choice. It was Joe Dodds, McMenemy’s old friend. They went back a long way, Jimmy having been the best man at Joe’s wedding and both, by a macabre coincidence having lost a brother at the Battle of Loos in 1915, but both having been persuaded by Maley to play in the Glasgow Cup final of October 1915 which Celtic won, beating Rangers 2-1.

Jimmy Napoleon McMenemy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

There is another famous photograph of Jimmy taken after the end of the Scottish Cup final of 1937. Seagulls are hovering over the now deserted Celtic End and the two goal scorers Willie Buchan and Johnny Crum are holding the Cup. Maley is almost breaking into a smile, Jimmy Quinn in the middle is clearly not smiling – but then he never did – but McMenemy at the end of grinning like a Cheshire cat.

It would be interesting to know if Jimmy McMenemy played any part in the interesting decision to allow Willie Buchan to go to Blackpool in November 1937. It was controversial at the time, but it earned Celtic some £10,000 and Celtic had an immediate replacement in Malky MacDonald. One suspects that Maley had at least talked to McMenemy about it.

It was certainly, in the long term, the right decision, for MacDonald was a great player, and certainly spoke highly of what he had learned from Napoleon.

Maley eventually parted company with Celtic in 1940. McMenemy would have been 60 in that year, otherwise he might have been considered for the job as his successor. In the event, the Directors went for Jimmy McStay, and for one reason or another, McMenemy quietly disappears from the scene.

He lived for another 25 years, eventually passing away in summer 1965 after Celtic had begun to return to greatness under Jock Stein. He was well-known and well-loved at Celtic Park, being allowed, for example, along with his old friend Davie McLean to join the party in the Hampden dressing room after the 7-1 win over Rangers in October 1957. He was a frequent attender at Parkhead, although the dignity of old age meant that he was now wearing a soft hat rather than a bonnet.

There was one rather remarkable reunion. In October 1963 in one of Celtic’s first ever forays into Europe, they were drawn against Basle of Switzerland in the European Cup Winners Cup. They had actually played this team before on May 27 1911 when Celtic on tour had won 5-1. One of the Basle players that night, one Ernst Kaltenbach, heard that Jimmy McMenemy was still alive and flew to Glasgow with the Basle team in order to meet McMenemy again.

They duly met, and watched the game together. It was a night of absolutely foul weather and Celtic won easily 5-0. McMenemy joked that if Ernst had been playing, he would have scored a consolation for Basle.

Jimmy died in Robroyston Hospital at the age of 85. He was described as a Wine and Spirit Merchant and is listed under his real name which was James McMenamin. He died of chronic bronchitis and a cardio-vascular accident, and he seems to have been ill for some time. A strong case can be made out for, given his playing career and then his coaching commitment, that Jimmy Napoleon McMenemy was one of the greatest Celts of all time, if not the actual greatest.

David Potter

Celtic in the Thirties by Celtic Historian Matt Corr is published in two volumes by Celtic Star Books. ORDER NOW!

Click to order Volume One

Click to order Volume Two

More Stories / Latest News

Live