Rosenberg's Reflections

·18 April 2021

The Offside Rule is Bollocks

In partnership with

Yahoo sportsRosenberg's Reflections

·18 April 2021

If you’re like me, you sometimes wake up at 7 a.m. on Saturday after a long week at work to watch Arsenal lose in a heartbreaking way. (Keep the faith, Gooners—we’re making slow progress.) And if you’re like me, you yell at the screen when the referee gives a perplexing offside against your team.

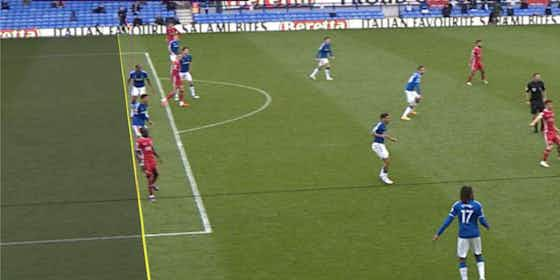

There are two problems with the offside rule. The first is intimately related to Video Assistant Referee (VAR), a recently-introduced instant replay system. Now, every scoring play is reviewed by video. The application of VAR sometimes leads to absurd results. Now, beautiful team goals that appeared perfectly legal in real time are sometimes called off because— it turns out when VAR combs over the video—in the build-up a player was offside by a whisker. Here’s an example. Liverpool (in red, attacking right to left) scored shortly after the left-most Liverpool player received a pass from a teammate off the screen to the right. But the goal was ruled out for offside.

Although that problem is significant, this article is about a separate problem.

The second problem is that the offside rule is especially unclear and unevenly applied with respect to players in offside positions who affect a play other than by receiving a pass. There are myriad and unpredictable game scenarios involving such players. For instance, a player in an offside position might: partially block the goalkeeper’s vision of a shot; challenge (or otherwise impede) an opponent; or affect an opponent’s defensive positioning by his mere presence or gesture towards or away from the ball.

A recent example epitomizes the problem. Manchester City (light blue) is attacking right to left. The ball is falling to an Aston Villa defender having been headed towards goal by the Manchester City player on the far right of the frame. The left-most Manchester City player is in an offside position.

That player comes back from his offside position to steal the ball from the Aston Villa defender.

Manchester City scored moments later. Even though common sense and intuition confirm that the offside Manchester City player obviously should have been flagged for offside, he was not. (In the following days, the relevant governing body confirmed that the referee made an error.) In my view, the referee so clearly erred because the offside rule as applied to scenarios like this is needlessly complex.

As already mentioned, a player in an offside position might influence a play in any number of ways that are difficult to predict. Still, the English Football Association attempts to catalogue precisely the game scenarios in which a player will be offside. The list is wordy, clumsy, and difficult to understand.

I propose that the rule be simplified as follows: A player is guilty of an offside offense any time that player’s being in an offside position is a substantial factor in his team’s gaining an unfair advantage.

My rule draws on the concept of causation from tort law. (Disclaimer: This proposal comes from a very young, inexperienced lawyer.) Put simply, tort law attempts to fairly allocate losses that result from accidents. Only entities that cause another party’s harm will be held liable. The factual scenarios of tort law (e.g., slip-and-falls, car crashes, botched medical procedures, and more) run the gamut of human interaction. If tort law attempted to catalogue those scenarios and craft scenario-specific causation rules, law books would be ten times longer than they already are. And no matter how long the law books, unprecedented factual scenarios would always arise. Recognizing this, courts do not rely on scenario-specific rules to assess causation in tort cases. Instead, courts apply a simple, flexible, broad standard in every case: An entity can be held responsible only when its action (or inaction) was a “substantial factor” in causing the harm.

The analogy between the tort law causation test and my offside rule is clear. Just as the “substantial factor” test succinctly distills its basic purpose in a universally-applicable way, so too does my offside rule: Cherry-pickers should not be allowed to help their team succeed.

Relatedly, my rule is easy to understand and apply and avoids technicalities and verbosity, which lead to confusion. Under my rule, a referee need not remember esoteric rules— just a broad, common-sense standard. Coaches, players, and fans—although they will undoubtedly still lambast a referee’s adverse decisions—will not be confused: Either the referee thought the player in an offside position was a substantial factor in a subsequent unfair advantage, or not.

Further, my rule merely attempts to clarify the current rule and to make it more easily administrable. I see no reason why it is worse than the current rule. And trading an opaque rule for a common-sense standard reduces the likelihood that the offside rule will be egregiously misapplied, such as in the Manchester City example above.

To be sure, my rule is subjective: “Substantial factor” and “unfair” are both broad terms open to interpretation. But the current rule is subjective, too. Although the rule has the veneer of precision because it is wordy and specific, it is subjectively applied (and misapplied). In fact, I view my rule’s broadness as a virtue: It allows a referee to look at a particular game scenario and apply simple concepts that clearly encapsulate the basic purpose of the offside rule. Any fear of inconsistency in offside decisions under my rule is likely overblown. Just as case law helps clarify a broad standard’s application in particular scenarios, referees’ decisions from week-to-week will help elucidate the proper and improper applications of my rule.

No offside rule will be perfect. But adopting my rule would—at least—reduce the number of obvious refereeing errors (see the Manchester City example). And, by elevating clarity, simplicity, and common sense, I think it will result in fairer and more widely-acceptable decisions. It certainly will not be worse than the current rule, and it might be a whole lot better.

Joseph Rosenberg is a judicial law clerk in Connecticut and a long-suffering Arsenal fan.