The Celtic Star

·24 April 2024

The Celtic Rising: The day the world changed

The Celtic Star

·24 April 2024

The build-up to the Cup final is often a vital time. Both teams had something to pick themselves up from after last Saturday’s disappointments. Dunfermline Athletic were now out of the title race and Celtic’s performance had been truly abysmal with Jock Stein’s timeous statement about the need to clear things out and his promises to bring in new players not missing anyone and hitting the wall.

It was clear, however, that this was a decision for the future. At the moment, hardly anything in the whole world was more important than Saturday’s Scottish Cup final. For those in school, the “Highers” and “O” Grade exams were beginning. These were crucial, life-defining moments to so many people – but the Scottish Cup final was more so!

Jock Stein decided to take his squad to Largs on the Ayrshire coast from the Tuesday to the Thursday for light training before returning to Glasgow for a final training session on Friday. The 14 chosen were John Fallon, Ian Young, Tommy Gemmell, Jim Kennedy, Willie O’Neill, Bobby Murdoch, Billy McNeilll, John Clark, Jimmy Johnstone, Steve Chalmers, Charlie Gallagher, John Hughes, Bertie Auld and Bobby Lennox.

The squad surprises us from a modern perspective. In the first place, there are three left-backs in Gemmell, Kennedy and O’Neill, more than sufficient presumably but enough to lead to some speculation that one of them might be deployed as a left-half, allowing John Clark to play at right-half and then Bobby Murdoch could return to the forward line.

Speculation along these lines (and it did appear in certain areas of the Press) clearly did not understand Stein’s major positive move so far, namely the transformation of Bobby Murdoch from an ordinary to average inside-forward to a world class right-half.

But there was also no reserve goalkeeper. John Fallon thus went to Largs knowing that, barring injury, he was in the Scottish Cup final team. Ronnie Simpson was left behind at Celtic Park – he had only been brought in as a cover for injuries in September 1964 – and not for the first time, people began to speculate that Ronnie’s long and distinguished career, which had included two English FA Cup-winner’s medals with Newcastle United away back in 1952 and 1955 was coming to an end.

But it was not as simple as all that. Stein, never a great understander of goalkeepers, did not at this stage seem to rate Ronnie Simpson very highly. Indeed, it had been Stein when Manager of Hibs who had decided to transfer Ronnie to Celtic. But one thing was clear, and that was that John Fallon, that likeable redhead, would be in the goal at Hampden on Saturday.

There were others left behind at Parkhead for whom the exit door now seemed to opening; Hugh Maxwell, bought last November from Falkirk and who had never impressed apart from a brilliant early goal against his old club; John Divers, potentially a great player but always a little slow and who did not always give the impression of being too keen to get involved; Jim Brogan, whose time might yet come, it was felt, and John Cushley, who had performed adequately when McNeill was injured, but was never really likely to replace him.

Press releases from Largs emphasised that this was no strenuous training session. Phrases like “toning up” and “relaxation” were used. Indeed, the players at this stage of the season did not really need to be worked hard, and it was felt that a couple of days away from home and a break from training routines with different food would do them a great deal of good and would encourage team spirit and camaraderie.

It was an old ploy of Willie Maley and had brought the players and the club great benefits. Bertie Auld in The Scottish Football Book 11 tells how a photograph appeared of him wearing football boots on one of the greens of a golf course – but the studs had been removed!

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

What was a surprise was the public announcement of Saturday’s team as early as 11.00am on the Wednesday. Jimmy Johnstone, Willie O’Neill and Jim Kennedy were the unlucky ones, and thus the team was Fallon, Young and Gemmell; Murdoch, McNeill and Clark; Chalmers, Gallagher, Hughes, Lennox and Auld. It was in fact the team who had produced the two best performances since Stein’s arrival, namely against Motherwell in the semi-final replay and Hibs in the 4-0 League win at Easter Road.

The announcement, made in bright pleasant spring sunshine as the players had a light training session at the Inverclyde Recreation Centre (to which they walked from their hotel!), was designed to remove all the harmful speculation in the Press and elsewhere.

There were those who deplored the dropping of Jimmy Johnstone, but then again, Jimmy, although immensely talented, did not always produce the goods and it was felt that Steve Chalmers was a safer option. Chairman Bob Kelly, it was said, approached Jock Stein and queried his deployment of Murdoch as a right-half. Stein smiled respectfully to his Chairman but said that Saturday would show what a great right-half Bobby Murdoch was.

The team returned to Glasgow on Thursday at lunchtime, relaxed and fit, while on the same day news broke of a considerably less happy football club’s trip. Eight Chelsea players were sent home from their Blackpool hotel by Manager Tommy Docherty. They included Scotsmen George Graham and Eddie McCreadie, and although no great details were issued, the Press talked about “incidents” at the Blackpool hotel. It is not difficult to work out that this had something to do with alcohol and possibly some less than totally respectable Blackpool ladies, but it was a brave action for Docherty to take considering that his team, already winners of the League Cup, were still in with a chance of the English League, won this year in the event by Manchester United.

Friday passed uneventfully. Dunfermline did not yet name their team, but their Provost – the curiously named James Forker – announced plans for welcoming home his triumphant heroes, and the local MP Adam Hunter announced that he was having his “surgery” early on Saturday morning so that he could get to Hampden. Meanwhile, Gair Henderson of The Evening Times revealed his skill at prophecy.

He stated it would be “Dunfermline’s Cup” and “Hearts’ Flag” because the Fifers were “Ahead in Team Work” and “Hearts won’t slip now.” Gair Henderson (sometimes unfairly called “Gers” Henderson because of his perceived Rangers sympathies) was a fine football writer; Cassandra, (the daughter of the King of Troy who was always correct in her prophecies) he was not.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

And so the great day dawned. It was a bright, pleasant spring day, but it was not like any other spring day. Was this to be the day of deliverance, or was it to join the previous four Scottish Cup finals in its crushing disappointment? It was probably the case that Dunfermline were the better side – their League position certainly indicated that – but on the other hand, as the perspicacious Celtic supporters kept pointing out – they could not win last week against St Johnstone when they had to win to keep themselves in the League race.

Yet their men were all fit today and in Willie Cunningham they had an able Manager and tactician. They still had two men left from their win in 1961 – Alex Smith and Harry Melrose, whereas Celtic had five in Billy McNeill, John Clark, Charlie Gallagher, John Hughes and Steve Chalmers. But of course, the key thing was that Jock Stein had changed sides.

The journey to Glasgow for supporters that bright Saturday morning was animated with a surprising amount of conversation about who was going to win the League, rather than the Cup. There was still in 1965 among Celtic supporters a general respect (not exactly love or affection, however) for Hearts and a general dislike of Kilmarnock, who wore blue, were managed by Willie Waddell and had “kicked Billy and Boaby aff the park” that awful day last August at Rugby Park.

So if Hearts won, drew or even lost 0-1 today, they would win the League and that would not necessarily be the worst outcome in the world. “Ah dinnae like them, mind, but at least they are no’ Rangers!” Pleasure was then expressed at the almost total collapse of Rangers this season.

It was immediately obvious in the streets of Glasgow that morning as one disembarked at Buchanan Street railway station that there was a special atmosphere in the air. Lewis’s Polytechnic was full of green and white scarves, tammies and favours, and fewer black and white ones. But it was friendly with loads of banter. There are some teams’ supporters with whom Celtic fans get on well and Dunfermline were one of them.

Old grannies decked in the black and white were seen to put arms round wee Celtic boys, asking where they came from and what was their favourite TV programme, did they like the Beatles and of course the vital question of “Who was going to win today?” Old Celtic supporters told younger Pars ones that they remembered Peter Wilson becoming Dunfermline’s manager before the war. The young Dunfermline boys were impressed, but clearly did not have a clue who Peter Wilson was.

Lunch was consumed but not always digested. Such were the nerves and the excitement of the day. The lunchtime edition of The Evening Citizen was reassuring. “Even if, by some unkind quirk of fate, the Cup is not wearing green and white ribbons tonight, things will soon change at Parkhead,” but the focus was all on today.

At Central Station, awaiting the Blue Train (they might have changed the colour for one day!), we saw women with shopping, young men with cricket bats (they were getting a good day for the start of the season) and other people wandering around aimlessly as people sometimes do at railway stations, looking perhaps for friends of the opposite sex who had failed to appear, but the largest proportion of the crowd wore green and white.

The destination was Mount Florida. If the opposition had been Rangers, we would never have dared to take that train, for Mount Florida was at the western or “Rangers” end of Hampden. It would have had to be King’s Park, but that was not a problem today. A well-dressed man, a pleasant faced but somewhat apprehensive woman, and two wee boys with black and white Dunfermline Athletic scarves got on. It was clearly their first time at Hampden.

A group of beery green and whites came on and the Pars family feared the worst. But one of the Celtic chaps with few teeth bent down and said to one of the youngsters, “And what’s your name?” Before we knew where we were, the conversation was all about holidays in Fife, “my granny came frae a place called Cairneyhill (dae ye ken it?)” and “I hope we get a good gemme the day.”

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

The wee boys grew in confidence, said they didn’t like Rangers, and the father told everyone that he knew the Callaghan brothers who were playing for Dunfermline today. He also said that in their spare time, the brothers were Celtic daft – but that was hardly a great secret. A few other Celtic fans started singing a song which had a bad word or two in it – and one of the Celtic fans shouted “Hey! Cut it oot! There’s a wuman here wi twa young laddies!” His moral stance was somewhat undermined by the fact that some other women, dressed in green, were joining in the blasphemous and obscene singing, but it was a brave effort.

Meanwhile, the mother was being relentlessly chatted up by a Celtic fan who was not unattractive but clearly past the first flush of youth. We got all the usual Glasgow dance hall chat-up patter about her hairstyle and “I wish I’d met you before he did” jabbing his thumb at the now totally relaxed and smiling father. Not only that, but “the next time we’re in Dunfermline, ah’m comin’ roon tae your hoose for a cup o’ tea.”

The precocious older boy, clearly an expert in such matters, then said that Celtic would be at East End Park on Wednesday night – providing of course, that today was not a draw. There was then a general feeling expressed that today might well be a draw “like the lest time, aw’ for anither big gate.”

The train, which had seemed to be saying “Cel-tic” repeatedly on its whistle, arrived at Mount Florida. The Dunfermline family were all wished well, the mother by no means discouraging of a wee kiss from the Celtic charmer, and the two wee boys were clearly in awe of Celtic supporters at their best, and repeated their feelings about not liking Rangers, while adding Falkirk and Raith Rovers to their list of un-favourite football teams.

It was great to walk up to Hampden Park in the dry on a fine day. No mud, no urine and your shoes unsullied. That old North Stand was showing its age, though, wasn’t it? But five shillings (no Boys Gate) was the price for admission to the Celtic end – that massive area of terracing which had seen so much action in Scottish football history and was destined to see a great deal more today.

Two things struck me about the view from the top of the Celtic End, and they were to do with what was happening away from the pitch. One was the amount of “dead body” fans who had not managed to get into the ground in a totally vertical position and had collapsed through the sheer amount of drink that they had consumed!

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

They were laid out gently but thankfully by their friends on the banking at the back of the terracing, and lay there, presumably, for the duration of the game! I counted about 12 such people and wondered how it was possible for anyone to get themselves more or less comatose with drink on a day like this! And what would have happened to them if it had been raining?

And the other thing I saw was a sight that excited both pity and envy. Behind Hampden at the Celtic End in 1965 were allotments for those of the horticultural persuasion. I looked down and I saw a man who was planting potatoes, or whatever one does with allotments.

My contempt for this man – how could anyone work in a garden a hundred yards away from this? – soon changed to jealousy when I considered the state I was in, quivering like a jelly, perpetually needing the toilet and finding it difficult to resist the temptation to be sick. This man on the other hand, with his braces holding up his trousers and his old jacket and bonnet hanging from a post, was working away in total relaxation although it must have been difficult with all the noise around him.

But now the ground was filling up. We knew that the crowd becomes less condensed the further down you go, and the late arrivals are often crushed so we tried to descend the mighty terracing which was becoming more congested by the minute. A group with no scruples pushed its way through singing the song about the lorry load of volunteers who approached the border town on New Year’s Eve eight years ago. We grabbed a hold of one of their flags, followed them down and got a good view.

The tension was palpable. Apparently, the radio at lunchtime had mentioned a rumour about an unexpected injury in the Celtic camp. This was discussed at length, but when the team was announced it was as expected. I had a look at the supporters near me, some clearly veterans of the Cup finals of Jimmy McGrory and Patsy Gallacher, many now approaching middle age who recalled Charlie Tully, many like me who had not yet had any clear recollection of them ever having won anything, and some even younger.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

There were men and women – the women often more garishly dressed in green than the men, again some old, some young, some trying to look younger than they were – but everything had this in common – the stress and pressure on their faces. “We’ll forgive everything, Cellic, everything, if ye’s jist win the day.” There had indeed been an awful lot to forgive.

The Evening Times reports some strange behaviour by the Dunfermline Manager Willie Cunningham. The team bus arrived well over an hour before kick-off and the party of 16 players were all hustled into the away dressing-room (Celtic had won the toss for the home dressing-room, apparently) and stayed there until they emerged down the tunnel at 2.55pm. The Directors went upstairs for their refreshments with their Celtic counterparts, but the players were nowhere to be seen.

Just what was behind this, we cannot tell. Maybe Cunningham had not yet finalised his team selection; maybe he just did not want them talking to the Press; maybe he did not want them to see the massive Celtic support, which was building up, but in any case, their players were deprived of their walk on the Hampden turf. No-one would have thought it significant at the time, but Pars’ centre-forward Alex Ferguson was dropped, presumably being blamed for Dunfermline’s inability to beat St Johnstone last weekend. It must have been a major blow for the youngster, whose playing career in Scottish football did not always enjoy the best of luck nor the greatest success. The team chosen, however, was the team that had beaten Rangers some ten days ago, and it was clearly this one on whom Dunfermline placed their major hopes for success.

Celtic on the other hand, their team having been picked and briefed, were able to have a short stroll on the pitch. It was not the habit in those days to have a warm-up on the pitch as they do now, and they were all in civvies as they waved to the crowd, giving the impression of being totally relaxed, a relaxation that presumably they did not feel.

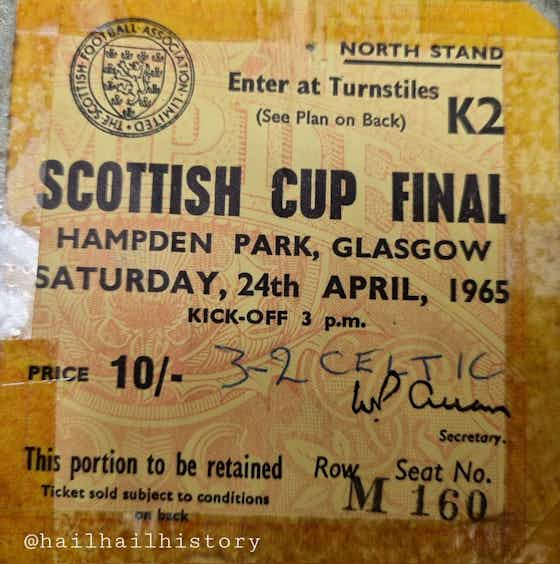

The teams that appeared were as follows;Celtic:Fallon, Young and Gemmell; Murdoch, McNeill and Clark; Chalmers, Gallagher, Hughes, Lennox and Auld.Dunfermline Athletic:Herriot; W Callaghan and Lunn; Thomson, McLean and T Callaghan; Edwards, Smith, McLaughlin, Melrose and Sinclair.Referee: Mr H Phillips, Wishaw.

Billy McNeill won the toss and elected to play towards the King’s Park end. The actual 90 minutes are of course well reported in contemporary newspapers and are available on YouTube, but they do not begin to convey the sheer emotion involved on that day. The standard of football by both sides was amazingly high considering all that was involved, and the Celtic performance, particularly in that second half was such that quite a lot of Celtic supporters given to mysticism wondered whether it was all “meant.”

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

One recalls the statement of the Second World War veteran who had played his part in the liberation of Italy, as well as other great Celtic triumphs involving Jimmy McGrory and Patsy Gallacher in the past who stated quite calmly in reference to the events of 24 April 1965 that he had “never seen anything like that!” Frankly, money could not buy the memories that day produced.

But to the game itself. It started briskly and Celtic playing with the wind had the better of the opening exchanges. Dunfermline’s centre-half Jim McLean was warned for a rough tackle and then John Hughes had a good run. One or two shots went wide or high, and it was clear that nerves, as one would expect in a Scottish Cup final, were playing a part. We also knew that there was a long way to go. It would be nice to take a lead, but we also knew that it wouldn’t necessarily decide the issue.

In the event, it was Dunfermline up at the distant end who scored first. It came from a throw-in which Thomson then hit up the field to Sinclair who knocked the ball on to Harry Melrose who in turn hooked the ball into the roof of the net. It was a well-taken goal, but it could easily have been prevented with a little more concentration.

The knots of Dunfermline supporters (Celtic supporters would have outnumbered them by about 20 to 1 at a conservative estimate) cheered their early lead, but for Celtic supporters, that sinking feeling, that all too familiar emotion in the early to mid 1960s, began to manifest itself once more.

We were aware that there were still about 75 minutes to go, and that there really was plenty of time, but we were also aware that the loss of a second goal could effectively kill the contest. Funnily enough, that loss of the goal seemed to settle the Celtic players, but the equaliser when it came was an unusual and dramatic one. It came originally from the boot of Charlie Gallagher, who picked up a pass from John Clark in the middle of the Dunfermline half, made a few yards and shot for goal.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

Those of us clustered behind that goal had a brief moment of seeing the ball heading towards us, and we were all set to cheer a great goal, but the cheers turned to anguish as the ball hit the bar and soared up into the air. It might have soared out of play for a goal kick, but here the capricious wind played its part, for the ball went straight up into the air, and the ever-alert Bertie Auld took his opportunity to get there before any of the Dunfermline defenders. Thus, Celtic were back on level terms as that terracing behind him erupted into ecstasy.

That was in the 30th minute and Bertie had to be disentangled from the netting, just like Patsy Gallacher in his great Cup final of 40 years earlier. Now we felt that we might get somewhere. We might now be able to even get ahead before half-time, but sadly it was not to work out like that, for it was Dunfermline who scored again just before the interval. Young was adjudged to have fouled Sinclair a few yards outside the penalty box. It looked like a fair challenge from the far end, but Mr Phillips was in no doubt. It was a dangerous position, and the Celtic defence lined up to face what they thought was going to be a shot from Melrose.

But Melrose tapped the ball to John McLaughlin, and at that very point the public address system started to make a pointless announcement about something to do with the imminence of half-time. No-one will ever know what it was all about, for McLaughlin hammered home a fine shot. To what extent Celtic were put off by that announcement we will never know – they certainly never complained about it after the game – but those around me in the Celtic end were convinced that it was a distraction, and the more paranoid thought it was all deliberate!

Half-time came soon afterwards with the Pars all cock-a-hoop at their team going in 2-1 up at the break. The Celtic community was stilled. We had been built up and now we had been knocked down again. There remained another 45 minutes of course, but it was still a depressing experience. Jim Farrell, the Celtic Director (and father-in-law of Jim Craig) tells the story about how he was on his way to the Directors’ Lounge along with Mrs Stein. She was of a different religious persuasion to her husband and tended towards Rome rather than 121 George Street, Edinburgh. She said as a joke to Mr Farrell that a prayer to St Anthony might be no bad thing. St Anthony, apparently, had jurisdiction over things that were lost, (like a house key or a wallet, for example) but might yet be still found. “Celtic were like that at the moment,” thought Mrs Stein.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

Far away from such theological and celestial speculations, more concerned with the mundane and the pressing, we on the East Terracing made a big mistake. We decided to go to the toilet. Quite a few men did not bother about such niceties, and simply did the necessary where they were, but we were of a decent family and made our way to the none too hygienic toilets.

One had to climb the huge terracing and descend the steps at the back to try to get there. It was a crush, but we managed it. The problem, however, was then that we could not get back in. It would remind the learned of Virgil’s Aeneid, when Aeneas was told that there was no problem getting down to the Underworld. The problem was getting back! “Hic labor, hoc opus est!” We certainly could not get back to our old places and were condemned to watch the second half from the top of the terracing where heads and other things got in our way.

It was not entirely without its advantages. One certainly got a fine panoramic view of the distant proceedings, both of the ground and the surrounding streets, and the amount of the “out of the game” drunks still lying on the banking. The allotment gardener was still there with a spade and a wheelbarrow, and once again, I envied him. No-one was bothering him; he was not bothering anyone, although he cannot but have been aware of the passion, the drama and the noise going on not all that far away from him. Maybe he had a transistor radio with him.

But we still had the problem of seeing the game. Celtic equalised through Bertie Auld (who else?) after a fine one-two with Bobby Lennox, but our view of it was obscured by heads. We came out of the terracing and walked along the path at the back before we eventually managed to get a reasonable view of the action holding on to the post numbered “25” at the very back of the terracing.

Beside us stood a black man – not all that usual in 1965 Glasgow – a refined soft-spoken gentleman, and a few youngsters, and we actually had a good view once the crowd settled down. We saw Fallon’s great save from Alex Edwards, which seemed to have got behind him, and we saw Clark getting something stuck up his nose after a facial knock, and we saw the battle raging.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

Dunfermline used the wind rather badly, often over-kicking the ball and putting it too far ahead of their forwards, while Celtic played more sensibly against the wind, keeping the ball low and with Auld and Murdoch in the middle of the field spreading passes to Chalmers, Hughes and Lennox. Celtic were having more of the play, but if someone had offered a 2-2 draw and a replay on Wednesday night, I probably would have taken it – such had been the gut-rending emotion of it all.

Once again, I thought with envy of the gardener planting his potatoes and of my mother, who was no great football fan and was often amazed by the intensity of it all, quietly making her tea and listening to the radio commentary, more concerned about whether her wee boy would get home safely rather than who was to win the 1965 Scottish Cup!

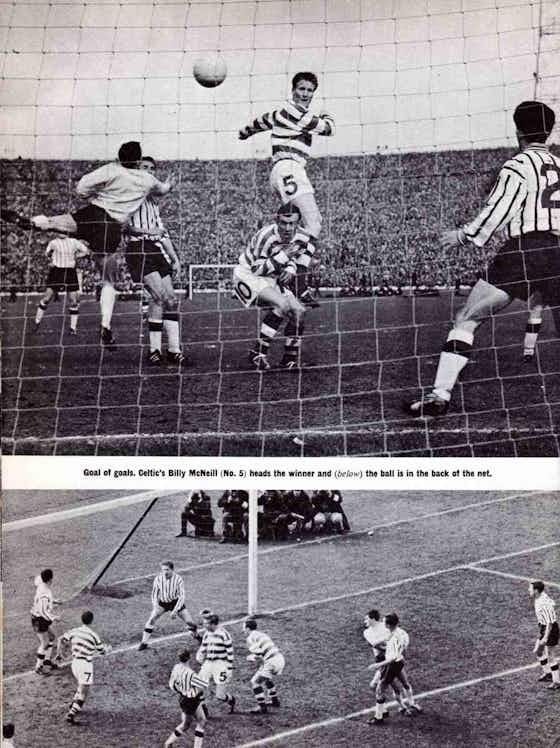

But then Celtic won a corner on the left after a run by Bobby Lennox. Across trotted the ever-reliable Charlie Gallagher to take it. One of the things that we had noticed since Jock Stein’s arrival in 1965 had been the increasing frequency with which Billy McNeill would go up for a corner kick. The Pars defence was not as prepared for it as they should have been, and Billy rose majestically to head home that magnificent iconic goal that changed everything.

I have no clear recollections of the goal, although I do remember thinking that it might have been Tommy Gemmell who scored (same colour of hair and I was, after all, about 250 yards away!) but the veteran beside me kept saying “Billy McNeill! Billy McNeill! Billy McNeill!” as we were engulfed in a tidal wave of celebration, scarves waving and people hugging you and jumping on top of you.

But there were still nine minutes to go. If I have no distinct recollections of the actual goal, I can recall with vivid clarity the last nine minutes. Flags waving all around the ground, a growing swell of noise, smiles, cheers but with myself holding on to the gangway 25’s post and unashamedly praying to God, whether he was a Catholic or a Protestant, to let us win today. Surely, we could not be denied now! But 10 years ago, Celtic had been 1-0 up in a Scottish Cup final against Clyde and had lost a last-minute equaliser from a corner kick.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

This kept going through my mind, as no doubt it did through the thoughts of so many people – possibly even Jock Stein who played in that game. They were perhaps better at hiding their emotions than I was but were undergoing all the agony just the same. Those who tried to tell me after the event “Ah knew we were OK when Billy scored” are, frankly, liars. Still more hideously wrong was the fatuous statement “It’s just a fitba match!” We still had these minutes to see out.

Bertie Auld did not seem to be worried though. He took his time, pretending to trip over a pile of police coats placed too close to the pitch, and generally clowning. In truth, Dunfermline seldom got over the halfway line in those last desperate minutes. I kept watching the linesmen. I knew that linesman signalled to the referee about how long to go, usually with their fingers against their black uniform and I kept looking for that.

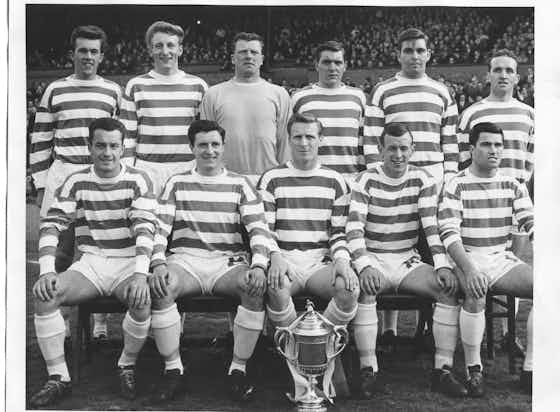

Eventually, I decided that there was no point in looking at anyone other than referee Hugh Phillips, and so I watched him obsessively as Celtic retained possession. Eventually he turned and pointed to the pavilion, and the immediate impression was of everything going up – players arms in triumph, flags, scarves and people – youngsters lifted up by their parents, arms in the air – and everything was green and white. And everything rose metaphorically as well. There was the glint of silver in the South Stand. This was what it had all been about – the Scottish Cup, and we had won something at last!

Tears welled up unashamedly, as the green and white figures appeared to collect the trophy, and out they came to get their photographs taken. Oddly enough, my feelings were for Dunfermline Athletic as much as anything else – a good team and their supporters were a decent bunch, and we knew what they were going through – and I joined in the polite applause for the Pars. But everything around me was going crazy, and I was particularly careful not to fall down the terracing stairs as the triumphant Celtic crowd swept out. There was no point in getting killed NOW!

The images remain – the seller of “The Shamrock” magazine “the long downtrodden man” as we called him, with a grin on his face instead of the hunted, persecuted look of before, and then the sight of a middle-aged, middle-class man, well-dressed with a tie and a soft hat and possibly a banker or a teacher during the week. He had collapsed over a hedge. He was not in any way under the influence of alcohol, nor did he wear any club colour.

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

Nor did he use any foul language as he looked at me and a few other bystanders and said with all sincerity and in measured tones, “I couldn’t have taken it if we’d lost the day!” And the two young teenage girls clad in green and white and singing – not The Celtic Song, nor Sean South of Garryowen but the Beatles “She Loves You! Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!” Incongruous, but there is nothing logical about ecstasy!

A few Pars fans were about, clearly disappointed but nothing nasty about them. Handshakes were exchanged and smiles and “We will see you on Wednesday,” a reference to the League game scheduled for that night, and one of them with a transistor radio told me that Kilmarnock had won 2-0 at Tynecastle. The implications of that one didn’t sink in until later, such was the all-consuming rapture of the moment.

The train from Mount Florida to Glasgow Central was noisy and overcrowded, dangerously so in fact but no-one cared. It was then, however, that real fear took over me that this might all be some sort of a dream and that I was going to wake up! Various thoughts of existentialist philosophy coursed through my mind, but they were soon driven out by the words of “the dreary New Year’s Eve” and “sworn to be free.” If I was going to wake up, so too would thousands of others!

CONTINUED ON THE NEXT PAGE…

But I didn’t waken up, and we got home by about 10.00pm after an idyllic and triumphant journey. The green and whites had returned. Parkhead was Paradise once more. Sunday was spent talking about nothing else, and the whole world had changed. Rangers and Hearts supporters avoided me – Hearts in particular, for that day was the start of untold miseries for them, but Rangers supporters as well knew that the game was up. Jim Baxter, their hero of the past few years, was beginning to play up and cause trouble again. Celtic’s success was one of those things that did not apparently have any direct connection with Baxter – but we all knew that it did. It was almost as if a switch had been pressed and for the next decade, with a very occasional exception, everything would run in favour of Celtic. The world had indeed changed.

It was like what Churchill said. “Before Alamein, we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat.” It was apparently based on something that Pitt the Elder had said of the Seven Years War, and it wasn’t 100% literally true – but it was close enough.

We felt similarly about Saturday, 24 April 1965. For the next ten years our defeats would be rare, and our successes would be repeated and indeed expected.

An extract from The Celtic Rising by the late, great David Potter

David’s bestseller The Celtic Rising ~ 1965: The Year Jock Stein Changed Everything is completely sold out in print on but is available on Amazon kindle, with all the photographs of the hardback edition, for HALF PRICE at just £3.49…