World Football Index

·13 June 2020

Fascism In Football: The Ugly Side Of The Beautiful Game

In partnership with

Yahoo sportsWorld Football Index

·13 June 2020

By Jack Beville.

Football has the power to bring people from different communities, backgrounds and beliefs together — both through the love of the sport itself and the culture that emerges from it. At the same time, however, the history of football is the history of rivalry and opposition.

In many cases, this takes the form of strictly sporting rivalry — the antagonism stems entirely based on what takes place on the pitch, the successes and the failures of the teams.

In other cases, the rivalry emerging from football culture and fanbases manifests itself in uglier ways.

Fascism, racism, and nationalism are part of the past and, regrettably, the present of football — the ugly side of what we endearingly refer to as the beautiful game.

Fascism is defined, in simple terms, as: “a governmental system led by a dictator having complete power, forcibly suppressing opposition and criticism”.

By this definition, a Fascist regime or an individual exhibiting Fascistic politics and beliefs is one who endorses an emphasis on “aggressive nationalism and often racism.”

Definitions of Fascism vary both in their detail and on their semantics though most, if not all, are rooted in the ideology of one historical figure in particular — Benito Mussolini.

Fascism, with its nationalistic repercussions, often uses populism as a means to appeal to the masses. It is unsurprising, then, that Mussolini, according to Bill Murray’s The World’s Game: A History of Soccer, “was the first to use sports as an integral part of government.”

Whilst Mussolini predominantly utilised the Italian national team in order to link sporting success to his regime — it is a widely-held belief that he had a personal soft spot for SS Lazio, and the feeling is mutual.

In 1987, in a game between Lazio and Padova, the fan culture and future of the former would be changed forever. Unveiled in the stands read a banner, introducing Italian football to Lazio’s new group of ultras — the Irriducibili. During the 1990s, the Irriducibili became especially notorious in the world of football.

A common theme amongst acts of hooliganism and intolerance from football fans, both individually and as a group, is the seemingly spontaneous nature of the acts themselves. In the case of the Irriducibili, this could not be further from the truth.

These are not acts that can be explained away, as is often the case in English football, by contending that they were acts of the idiocy of individuals. Lazio’s neo-fascist right-wing ultras became well-known for the choreography and the calculation with which their acts of violent intolerance were planned and executed. These acts are deliberate. These acts were diabolical.

The overwhelming majority of these acts from the Irriducibili have been directed at Roma fans. The clubs have always shared an intense rivalry, encapsulated whenever the time comes for another edition of the Derby della Capitale.

The rivalry is not simply a sporting rivalry. It has become one fuelled by the toxic Fascist politics of Lazio’s right-wing ultras.

Historically, Roma have always been the team supported by Rome’s small Jewish community. As a result, the majority of incidents directed toward the fanbase by Lazio ultras tend to revolve around anti-Semitic rhetoric, prejudice, and iconography.

Two major incidents during games between the two sides occurred in the late 90s and early 2000s. The first, when Lazio’s fans unveiled a 40-metre-long banner that read “Auschwitz Is Your Homeland; The Ovens Are Your Homes”. This incident requires no explanation. It was nothing other than a disgusting act fuelled by anti-Semitic hatred.

Unfortunately, and rather unsurprisingly, this wouldn’t be the last. In 2001, during a game in which Roma’s Cafu and Jonathan Zebina were frequently subjected to racist abuse whenever they were in possession, the Irriducibili unveiled a banner with the message “Black team, Jewish supporters”.

Elsewhere, the Irriducibili offered their endorsement to Željko Ražnatović in a 3-1 win against Bari in 2000. Ražnatović, known as ‘Arkan’, was a Serbian indicted war criminal who was prosecuted on 24 charges of crimes against humanity. Arkan, through his paramilitary group the Tigers, advocated ethnic cleansing. Lazio’s fans, following his assassination earlier that year, held up a banner reading “Honour to the Tiger Arkan”.

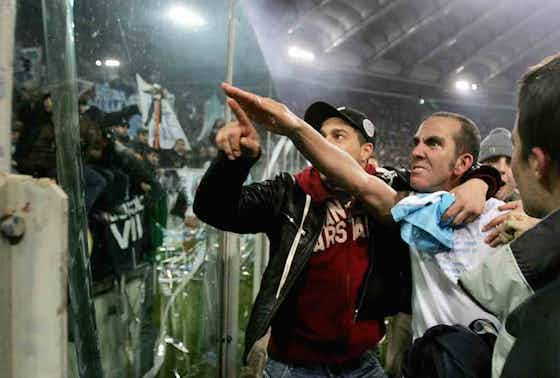

Unfortunately, the issue remains today. Lazio’s stands are still rank with Nazi and Fascist symbols and messaging. Swastikas, straight-arm salutes, celtic crosses, the Wehrmacht eagle, and taunts toward rival fans of “Jew”. All of these are still commonplace.

Less than three years ago, in October 2017, Lazio fans left stickers depicting Anne Frank in a Roma shirt alongside slogans such as “Roma fans are Jews” in the Stadio Olimpico — the two clubs’ shared ground. The act landed Lazio a fine of €50,000. To contextualise this, Huddersfield were fined more for a Paddy Power-related pre-season kit stunt.

More recently, in 2019, a day before the Italian celebration of Liberation Day, Lazio fans performed Nazi salutes and proudly displayed a banner honouring Mussolini himself. The banner was then hung nearby Milan’s Piazzale Loreto, the square in which Mussolini’s body, following his execution in 1945, was hung upside down. This image was, however, used against Lazio by Celtic fans in 2019 through a banner depicting Mussolini’s hanged body accompanied by the message: “Follow your leader”.

Any discussion or conversation regarding Lazio’s neo-fascist ultras cannot go without mention of one man; Fabrizio ‘Diabolik’ Piscitelli. It was Piscitelli who oversaw the Irriducibili’s rise, through his commodification of their extremism, and the unapologetic way in which he viewed it — telling James Montague: “We are a bunch of f***ing bastards, basically”.

Through Piscitelli and his business empire ‘Original Fans’, the Irriducibili became able to spread their message, promoting on scarves, stickers, and badges. Fascist paraphernalia rapidly became commonplace. Piscitelli was a powerful man, with links and connections to other dangerous people, including but not restricted to Italian organized crime syndicate the Camorra.

Piscitelli’s life came to an end in 2019 when he was assassinated. Six months later, on the 27th February 2020, the Irriducibili disbanded.

Lazio’s history with Fascism found its way into Premier League conversation when, in 2013, Sunderland appointed former Lazio player Paulo Di Canio, who knew Piscitelli, as their manager. Di Canio had played for Sheffield Wednesday, West Ham and Charlton prior to this appointment, but his stints at these clubs predate the allegiance to Fascism he would affirm in his second spell at Lazio.

Di Canio, who has a tattoo of Mussolini on his shoulder and had, on numerous occasions, saluted Lazio’s right-wing fans, unsurprisingly refused to deny the fact that he was a Fascist in multiple press conferences.

Di Canio’s brief spell at Sunderland lead to huge opposition from the Durham Miners’ Society and led to former Labour MP and Foreign Secretary David Miliband resigning from his role as Vice-Chairman of the club.

Mussolini’s Lazio represent one of many instances in which a prominent political figure has endorsed a football club as a means of promoting a particular regime, or as a way of attempting to symbolise the country’s success generally-speaking, General Franco’s influence in Real Madrid’s history being another significant example.

This, however, is not always what leads to club-adopted far-right extremist views that embed themselves within the fan culture connected to a club.

Other cases involve the very conception of the football club arising in highly politically charged locations, or the agendas and intentions of those who founded the club originally.

For such clubs, the embrace of racist, far-right beliefs is seen to be synonymous with the preservation of club-specific tradition. Something necessary to maintain the heart of the club. This brings us to two clubs specifically; Beitar Jerusalem and FC Zenit Saint Petersburg.

FC Zenit Saint Petersburg’s most prominent and infamous supporters’ group, Landskrona, are renown for their vitriolic views on race that they have repeatedly, and rather unsuccessfully, attempted to deflect criticism of through the explanation that they are simply trying to protect the club’s tradition.

In this sense, as is often the case with racial discrimination, the prejudice hides under the mask of patriotism, of identity. Writing a now-famous manifesto in the early 2010s, Landskrona implored Zenit to refrain from, and to explicitly avoid, signing black and/or homosexual players. This, of course, received global backlash.

In the manifesto, formed as an open-letter, Landskrona expressed their belief that black players were being “forced down Zenit’s throat”, and that homosexual players were “unworthy of our great city”.

Distancing themselves from any possible, though not at all erroneous, interpretation of such statements as being blatantly racist, the leader of the fan group Alexey Rumyantsev doubled down on this idea of cultural preservation: “Racism? No. I was just taught in school: blacks should live in Africa, Indians — if there are any left — in America, Chinese — in Asia. And then they can all visit each other… but only to visit, not to stay and bring their habits and laws with them. I want the outskirts of the city to be St. Petersburg, not Baghdad, Nigeria or whatever else.”

Racist rhetoric is commonplace in the stands and in the footballing culture in Saint Petersburg — symbolised by the fans’ mantra that “there is no black in the colours of Zenit”.

Make no mistake — there is no hiding behind the fact that this is racially-motivated. To buy the lie, no matter how deeply Landskrona may have allowed themselves to believe it, that such views seek simply to maintain the culture of the club and city is to ignore the fact that such views hardly differ from eugenics at all.

Zenit’s fans do not simply express these views away from the football pitch, through manifestos and letters mimicking some form of political measure. They take these matters further to the Gazprom Arena — lovingly named, for sponsorship reasons of course, after the multinational energy corporation that has fuelled Zenit with an almost-bottomless pipeline of money.

To list every incident of racism from Zenit’s ultras would require a piece of writing of its own, of biblical proportions. In this case, there are two more recent cases that epitomise the issue in Saint Petersburg.

In a Europa League tie between Zenit and RB Leipzig in March 2018, Zenit fans targeted Naby Keita, now plying his trade at Liverpool, after he was struck in the face by the ball. The chant from the fans of “we killed the negro” landed the club a fine of €50,000 and an order to play a qualifier behind closed doors.

Most recently, Zenit fans were especially outspoken in protest over the club’s signing of Brazilian winger Malcom from Barcelona. Their protests included banners reading an array of references to Landskrona’s original manifesto — such as “RIP Selection 12” and “thanks to the leadership for loyalty to the traditions”.

Once again, the response from the Zenit fanbase revolved around dodging accusations of racism. To anybody who believes that these incidents aren’t indicative of flagrant racism — I have a bridge to sell you.

Beitar Jerusalem’s idea of keeping in with the tradition of the club revolves around staunch opposition to both Muslim and Arab players, exemplified by the fact that in 2013 when Beitar signed Zaur Sadayev and Dzhabrail Kadiyev, the fans responded by chanting “Muhammad is a homosexual” and “Death to the Arabs”.

La Familia, Beitar’s most prominent and fiercely anti-Arab and anti-Muslim fan group went further still, setting fire to the club’s offices and leaving the stadium when either player scored. When club captain and goalkeeper Ariel Harush took to social media to voice his support for both players, he then became an object for abuse. He, too, was run out of the club.

In 2004, loan signing Ibrahim Ndala, a Nigerian defender, made four appearances for the club before leaving only six weeks into his loan. The reason? Intense racially motivated harassment by La Familia. He later told Sport 5 that: “No Muslim or black player should play at Beitar”.

As recently as 2019, La Familia responded to the club signing Ali Mohamed, a Christian from Niger, by suggesting that his name be changed for, essentially, sounding too much like a Muslim. In a swiftly-deleted social media post, La Familia stated that, while they accepted his Christian faith, they had a “…problem with his name. We will make sure that his name is changed so that Mohamed is not heard.”

The club itself has a long history of links to Zionist and right-wing political groups and movements such as Irgun, for example — a Zionist paramilitary group that operated in Palestine in the 1930s and 40s.

Formed with Zionist intentions, the club is also backed by the vocal support of Benjamin Netanyahu, the current Prime Minister of Israel and a high-profile right-wing politician — leader of Likud, a conservative and nationalist party founded upon revisionist-Zionist ideology.

To make the assumption that this kind of hatred is strictly a problem overseas would, however, be a mistake. A grave one at that. It is undeniable that English football and the fan culture that it breeds have a longstanding issue of racism, whether it be at club or international level.

In a domestic sense, the Premier League has always struggled with racist abuse directed at players from fans. Speaking to CNN in early 2020, Sanjay Bhandari, chairman of Kick It Out, explained the issue facing English football;

“Football is very different to what it was in the 1970s, racism is not the endemic thing that it was in the 1970s […]

“Over a 40, 50-year period? We’ve definitely [made progress]. But it’s worse than it was five years ago, and it’s worse than it was seven years ago.”

Fascism and racism are both issues in football that stem out of one of the very things that make the sport itself the global attraction it is, and what makes the sport so engaging as a fan — the fans themselves.

Football without fans is, as we are so often told, nothing. Though fan participation, and so too that of players, should never come in spite of a barrage of vitriolic abuse fuelled by political and racial prejudice.

Football is, of course, the beautiful game – but it has an ugly side that we simply cannot ignore.

Live